Expensive Knowledge

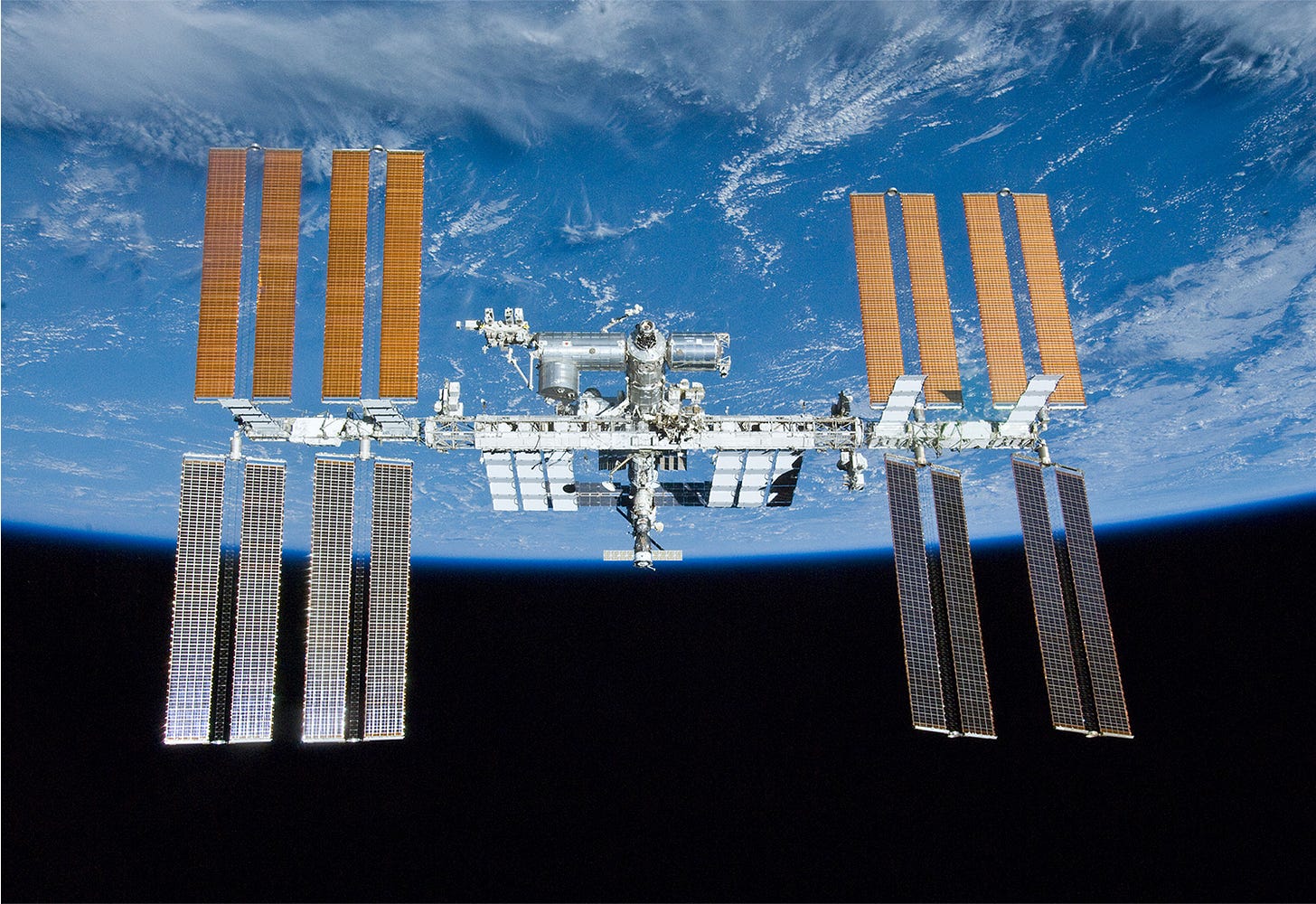

(Photo of International Space Station from NASA)

BBC seems to have forgotten about putting me on the air to talk about certain painful anniversaries, which is fine. Those mini-interviews hurt. Most of the time I’d rather talk about plans to go to the moon again or to Mars, or talk about how much we’ve learned about the Earth by looking at it from up above.

For whatever reason, when a crew of NASA astronauts dies, it’s usually at this time of year.

27 January 1967, the Apollo 1 preflight test fire that killed a crew of 3

28 January 1986, the Challenger disaster, killing a crew of 7

1 February 2003, the Columbia re-entry disintegration, killing a crew of 7

Some articles and posts show up every year to honor the astronauts who died then, and rightly so.

But the astronauts who survive their flights pay a cost on behalf of the rest of us that is seldom discussed, especially when their flights are long. They give up some of their health. When admitted into the astronaut corps, they are exemplars of human fitness. After even one longish flight, they pay for it, often for the rest of their lives.

They aren’t the type of person to complain.

What they’ve done was exhilarating and priceless. We wouldn’t have learned nearly as much if we limited space flight to machinery without ever sending humans. It’s difficult and dangerous to send them up there. Staying up there for a long while harms them. But humans can notice things that machines and cameras miss. Humans can adapt. Humans can observe and think about what they see and bring back insights a machine cannot. We need both types of missions, with and without a crew. They have gained crucial knowledge for us that we need in order to have any chance of saving our world from ourselves.

What do I mean when I say the crew is harmed? What do they give up for the sake of scientific discoveries that can help us all?

Cosmic rays are radiation. Astronauts go outside the protective envelope of our atmosphere and most of the magnetic field, so they get exposed to radiation. That increases their odds of developing cancer, cataracts, heart disease and other degenerative illnesses.

Weighlessness (technically, microgravity) has all manner of effects on the human body. We’re designed to live in gravity. Without it, fluids are more evenly distributed through our bodies. That makes faces puffy in orbit, for example. Eyesight changes in space, and sometimes it doesn’t snap back to normal upon return to Earth. Muscles don’t have to work so hard and lose strength. That includes the heart, perhaps the most important muscle we have.

Bone is a piezoelectric substance. Bend a chicken bone in a dark room and if you’re looking closely, you may see a tiny spark. Simply walking and lifting things in gravity bends our bones a little too, triggering a tiny piezoelectric effect. Somehow that appears to be involved with how our bodies destroy and rebuild bone.

Get rid of gravity and that cycle is messed up. We aren’t getting the piezoelectric signals to build bone. Calcium leaches out (raising the risk of kidney stones as it is excreted in urine). The usual rebuilding is not happening, so bones become weaker.

Genes get switched on or off. Changes occur at a cellular level that in some ways resemble aging.

Systems change too. I’ve seen a science fiction movie where a latent virus reactivates in an astronaut and the rest of the crew is at risk from it. The virus in the movie spreads via body fluids, and the movie pretended it was airborne to generate more drama. (My wife asked again why I ever watch movies like that when I’ll end up ranting where they get the science wrong.)

But the general concept of reactivation is based on reality. Studies suggest the immune system may not work in space flight as well as it does down here. Specifically, efficiency falters in a portion of it which normally suppresses viruses that cause such diseases as chicken pox or mononucleosis.

The vast majority of people carry at least one virus like those which never completely go away, instead being forced by the immune system to go quiet. Shingles is what you get when the virus for chicken pox reactivates. Epstein-Barr Virus has recently been implicated in multiple sclerosis. Reactivation in an astronaut on a long mission would not magically resolve as soon as they come back to Earth.

Neither do some of the other adverse effects on astronauts’ bodies, which I’ve barely given a light once-over here. Think about someone you know who has osteoporosis, then imagine coming back from a six or twelve month tour of duty with, say, a few years worth of bone density loss in the prime of your life.

This is how much astronauts love science, the quest for understanding, the need to better comprehend the world we live on and the solar system in which it spins. When they fly on a mission, they know they might die. They also know if they survive the mission, they will live with consequences all their lives.

They choose to pay that price. They do it on behalf of all of us.

I always admired astronauts. Now that we have better insight into what it costs them, I admire them even more.

--

A few articles if you want to know more:

https://www.nasa.gov/feature/scientists-probe-how-long-term-spaceflight-alters-immunity

https://www.nasa.gov/hrp/bodyinspace

https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/nasa-twins-study-reveals-health-effects-space-flight

https://www.space.com/23017-weightlessness.html

I had no idea bodies were affected so strongly from being in space. Eyesight changes were particularly odd, but I can understand it better now that you've explained it.