(Image from StackExchange)

Some people in business claim you can only manage what you can measure, so you need to measure practically everything.

Poppycock.

Sometimes Metrics Tell the Wrong Story

For one thing, not all measurements are edifying and some are downright misleading.

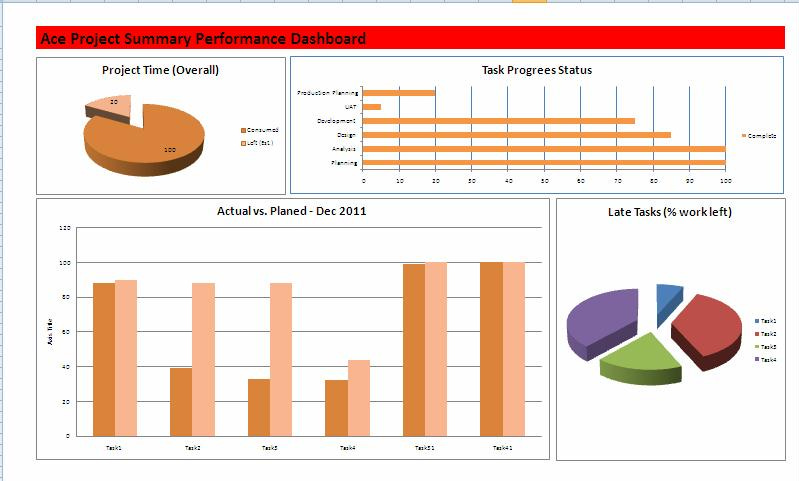

Here’s an example. I’ve been looking at dashboard software for project management. One of the measurements often touted is the number of issue tickets handled by each worker per day or per week. To show why this is a wonderful metric, I’m shown a list of people with that metric for them, often as a bar chart. The narrative tells me how easy this makes it for me to see which person is most productive.

I understand that this is a common way to look at the performance of customer support people answering calls, computer programmers fixing bugs, field service technicians doing repairs, and so on. It doesn’t really tell me who’s most productive.

Why? Because not all calls, not all bugs, not all repairs are the same.

The most difficult and complex tend to get handed off to the people who are best at handling the toughest work. It takes longer to do a tough piece of work than an ordinary one. Because the best problem solvers keep getting especially hard work, they can’t get through as many calls or bugs or repairs as the average person in their type of job.

The metric makes them look like they’re slackers. Meanwhile, the metric looks prize-winning for someone who only handles ordinary work and passes along the hardest pieces to someone else.

Can’t See Through a Blizzard

For another thing, if you measure too many metrics, the blizzard of measurements can smother what you’re supposed to be accomplishing.

Years ago, Temple Grandin (disclosure: affiliate link) crystalized this better than I’ve seen done by anyone else. (I don’t remember exactly which of her books I was reading and I give most books away after reading them due to limited storage, so the link I’ve provided is a bit of a guess. She’s a wonderful writer.)

Grandin had been brought in to help a livestock processing facility that just couldn’t keep itself running in top form.

When she got there, they showed her the metrics they were tracking every day. After all, as the saying goes, you can only manage what you measure… They were tracking a huge number of items.

That was their biggest problem.

Monitoring so many items was taking so much of their time and attention, the ones that were most important got lost in the blizzard of measurements.

Grandin narrowed it down to the few that would stay within a certain range when everything was going well, and would veer out of bounds when something wasn’t right. The trick to running the facility well was to monitor only those few items, only about a dozen.

If one of those few items strayed out of bounds, then it was time to monitor more details that affected the one which had slipped. That would reveal where the trouble was so it could be fixed. The facility had already accumulated reams of data about everything it could measure, so it knew what each detail should look like when operations were good. After the problem was fixed, monitoring would go back to only looking at the special few items.

Summary

Metrics can be very useful. They can tell us what’s going well and what needs improvement. They can tell us who’s doing great work and who isn’t. But that only happens when we choose them wisely and use them well. If we simply use the ones somebody recommends and interpret them the way somebody suggests, our metrics can be misleading or overwhelming.

The best managers don’t do everything by formula. They have some formulas but also apply good judgement. Part of that judgement is choosing what to measure, how to use the metrics, and where to draw the limits of their usefulness.

Lies, damned lies, and statistics.

Your data analysis is only ever as good as the thought and methodology behind data collection. If you're collecting the wrong data or the right data for the wrong reason, your analysis is useless at best.

There's always a balance between what can be measured and what can be observed or intuited. (Reminds me of Special Agent Gibbs, NCIS TV show and his famous "gut instinct.") I'm a fan of Temple Grandin - I heard her years ago on NPS (I think it was a Terry Gross interview) and saw the movie about her. I don't know what you mean by "affiliate link" though. She is an example of how a "disability" is a gift She also learned, from studying how to keep cattle less stressed as they are being led to slaughter, how to soothe herself with a squeeze box. Very enlightening.