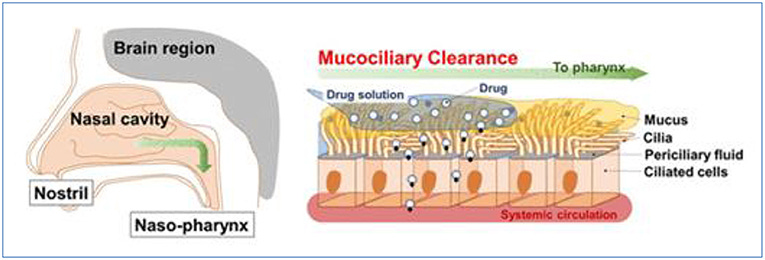

Occasionally someone asks whether I believe we will ever have a sterilizing vaccine against COVID—a vaccine that prevents infection with SARS-CoV-2. I can’t promise we will, but mucosal vaccines show immense promise in that regard. Coronaviruses infect us first and foremost through the mucus lining of the nose. If we can stop it there, the rest of the immune system won’t have to contend with it.

Most efforts toward a mucosal vaccine appear to focus on delivery via the nose, so I’ll use the term nasal vaccine here. A mucosal vaccine delivered in other ways is possible (for example, a lozenge would reach the nasal lining in the same way BLIS K12 probiotic lozenges do) but doesn’t appear to be as close to becoming available in either of my countries (UK and USA).

The golden prize would be a sterilizing vaccine (highly effective at preventing infection, not only reducing the severity of initial illness) that is pancoronavirus (works against all known coronaviruses and is likely to work against future coronaviruses), or at least against the subset of coronaviruses that includes SARS-CoV-1, MERS and SARS-CoV-2.

Immunocompromised people may not be able to safely take such a vaccine because their immune systems can’t respond normally to it. If practically everyone else takes a vaccine which is so good it prevents infection (and therefore also prevents transmission from one person to another), that should be enough to tamp down this pandemic… and then we will all be safe from it at last with little individual effort by most people.

First Places to Use Nasal Vaccines

The first countries I noticed approving nasal vaccines were China and India. When those vaccines were released, they were specifically intended to be delivered after needle-in-the-arm vaccinations. Ideally, this is meant to provide systemic resistance from the injection and mucosal resistance from the nasal vaccine. There were some other limitations on their use.

I was a little slow to notice what was happening. Other countries that were quick to approve nasal vaccines are Iran and Russia, and theirs were approved before China’s or India’s.

The first version of anything is usually not the best we can ever make, but somebody has to be first out of the gate. A few countries already took that initial step, and used theirs as boosters after jabbed vaccines that are known to be reasonably effective at reducing illness severity.

Other Development Projects

Other efforts toward a nasal vaccine, or in a few instances an oral vaccine, are underway. In which other countries? I’ve heard of such efforts in Canada, Cuba, Germany, Mexico, Netherlands, UK and USA.

I highly recommend clicking here to read a Health Central article about nasal vaccine efforts against SARS2. It does a good job of explaining key concepts in understandable language: reasons to make a nasal vaccine, how such vaccines work, and the two main approaches for creating such a vaccine.

Click here if you want to know more details about the status of various mucosal vaccine development projects and clinical trials as of about a month ago. Notice in the table near the end of the article that some have reported Phase 3 trial results. Getting there is significant. Many vaccines never get that far. They aren’t as good as what we want yet. We were desperate for whatever help we could get and got first generation vaccines in record time. Second generation vaccines have tougher goals to achieve. This takes time.

Personal Views

Do I expect one of the two approaches described in the Health Central article to perform better? My personal bet would be on the attenuated whole-virus approach to be more capable of recognizing new variants, new subvariants, and perhaps even other coronaviruses.

One of the key limitations of current vaccines is reliance on the spike protein. My wife has patiently listened to me grumble about that since the very first vaccines against COVID were released.

The spike protein of the virus mutates rapidly. That makes our vaccines quickly become no longer on target. It also doesn’t allow recognition of other coronaviruses. We have faced SARS-CoV-1, MERS and SARS-CoV-2 across less than twenty years. A nasal vaccine based on the spike protein can only protect strongly against the last of those, not the other two—and not the next one, which may be similarly dangerous. But a nasal vaccine based on the entire attenuated virus can protect against what we face now and have a good chance of helping us fend off the next coronavirus. A new strain can’t change nearly all of the virus at once.

We can keep our eyes on that prize, but we will screw it up if we rush too much. It’s worth our while to put in the work and take the time to get the next generation of vaccines as close as we can to what we want. If we do, we can make it as hard for coronaviruses to run wild with us as we do for polio… maybe even as hard as we made it for now-extinct smallpox.