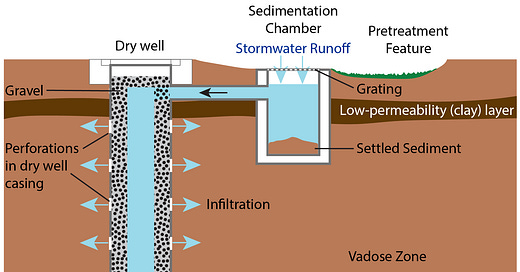

(Diagram by American Geosciences Institute)

The conventional answer here to our drainage problems is to install a soakaway. A soakaway is a single-chamber simplified version of what Americans call a dry well, a hidden cavity underground but above the water table (groundwater level) that runoff is directed into. Between rains, the water accumulated in a soakaway gradually drains away into the surrounding ground.

Our ground around this house gets so wet so quickly and stays wet for so long, when we do our first mowing of the season, everyone else near us quickly does theirs if they haven’t yet. The street echoes with a lawnmower chorus. When our grass dries out enough to mow with an electric machine, nobody else has an excuse.

This winter, a soakaway might have some merit. The UK just had its driest February in 30 years. But usually, it starts raining a lot in October and doesn’t pause long enough for anything to dry out until March. In most winters, our water table would be too high. A soakaway at our property would quickly fill with all the water coming through the ground from neighbors above us (never mind surface runoff). From then on, we would be no better off than before the soakaway.

Basic science to the rescue! We tied into the storm sewer system instead. That’s where the water is ultimately going anyway. We help some of it take a shortcut.

Mathematics came to the rescue, too. We needed simple math to calculate whether repurposing yellow square paving slabs from an outdoor table area would be enough to widen our entire patio. We needed math to calculate how many tons of gabion stones and slate chips to buy, and how much rubble to scrounge in order to complete the gabion wall without buying more gabion stone than we needed.

Science & Math are Useful Everywhere

We had to calculate how much lumber and hardware to buy to fence the veggie patch, put a fence behind the gabion wall and put a matching section of fence on the other side of the steps beside the gabion wall.

The question “what if my ground or ground water is toxic” is another example of how science can be pertinent to projects like our garden transformation.

Imagine being the local garage that said my failing clutch was an exotic cable and hydraulic hybrid system which would cost more than £400 to repair. They knew my background and tried such foolishness anyway. I tinkered under the hood so I could drive to the client site I needed to reach and got a proper repair done over there. The simple all-cable clutch system only needed a £35 part and 90 minutes of labor.

Knit Club does mathematics all the time, tweaking patterns to get exactly the look and fit they want. Some of them combine math with materials science and chemistry to produce yarn from fleece and dye the yarn. (Never spread out a recently shorn unwashed fleece indoors. The smell will knock you over. That’s where the two wool shop owners in Knit Club start, with unwashed shorn fleece.)

My sister does mathematics all the time, sewing, as did generations before her. V’s grandmother made her living as a seamstress. V makes most of her own clothes.

Knitting, crochet and sewing are, as V puts it, engineering with textiles. Physical traits of the materials affect the way they feel, drape, look, tolerate wear, cope with strain and survive laundering. Going from a pattern and bolts of fabric or skeins of yarn to garment requires lots of judgement and calculations. Even when it’s only a matter of making a set of curtains, all of that comes into play.

Basic science and basic mathematics come in handy over and over, often in mundane ways. Day to day, few of us need exotic science such as quantum mechanics or advanced mathematics such as calculus. But we usually don’t even realize how often we use a decent basic grounding in science and math for ourselves, our homes, businesses or projects.

Scaling Up the Stakes

Scale up the stakes and the need for a good basic grounding becomes much more important. Architects, builders and engineers rely heavily on science and math to design and build. When an architect or builder gets it wrong, an entire building can at best be not quite right, or even so bad it has to be demolished.

Among the amusing examples, my father used to have to visit an office in downtown Houston, Texas, on a regular basis. It was high up in 2 Houston Center. The building wasn’t quite right. From about the 16th floor up, on windy days it snapped, crackled and popped like a bowl of Rice Krispies™ in milk. The building was sturdy, in no danger of falling down, but being on an upper floor was an unsettling experience.

(Photo from Geograph)

Among other examples, the National Glass Centre in Sunderland isn’t old at all by British standards. Some people in the UK still live in cottages or houses built hundreds of years ago. The Glass Centre opened in 1998. It houses glassblowing workshop facilities and the Northern Gallery for Contemporary Art.

It is in such bad condition that it may have to be demolished. Remediation would require tens of millions of funding.

This is the type of consequence that happens when architects and builders get it wrong… or it can be worse. I won’t go into more catastrophic examples. Those make headlines in the worst ways when a bridge or building collapses.

National or International Scope

The stakes become even higher when governmental policymakers are involved. Policy decisions can affect an entire nation or have international consequences.

Being able to do clever science and mathematics yourself isn’t necessary to make good governmental decisions. Having a good grasp of basic science and math, being able to understand advice from experts and ignoring advice that pushes ideology ahead of science are essential. Some politicians strive to do that. Some don’t and some can’t.

With most policy decisions, there is plenty of room to argue about elements of decisions that aren’t underpinned by hard science. The interstate highway system in the USA, the National Health Service in the UK, or tuition-free university study in Norway produce results that show up in data, but not in ways that can be readily isolated. Each of those programs is deeply entangled with many societal and economic factors.

Narrow Focus has been Revealing

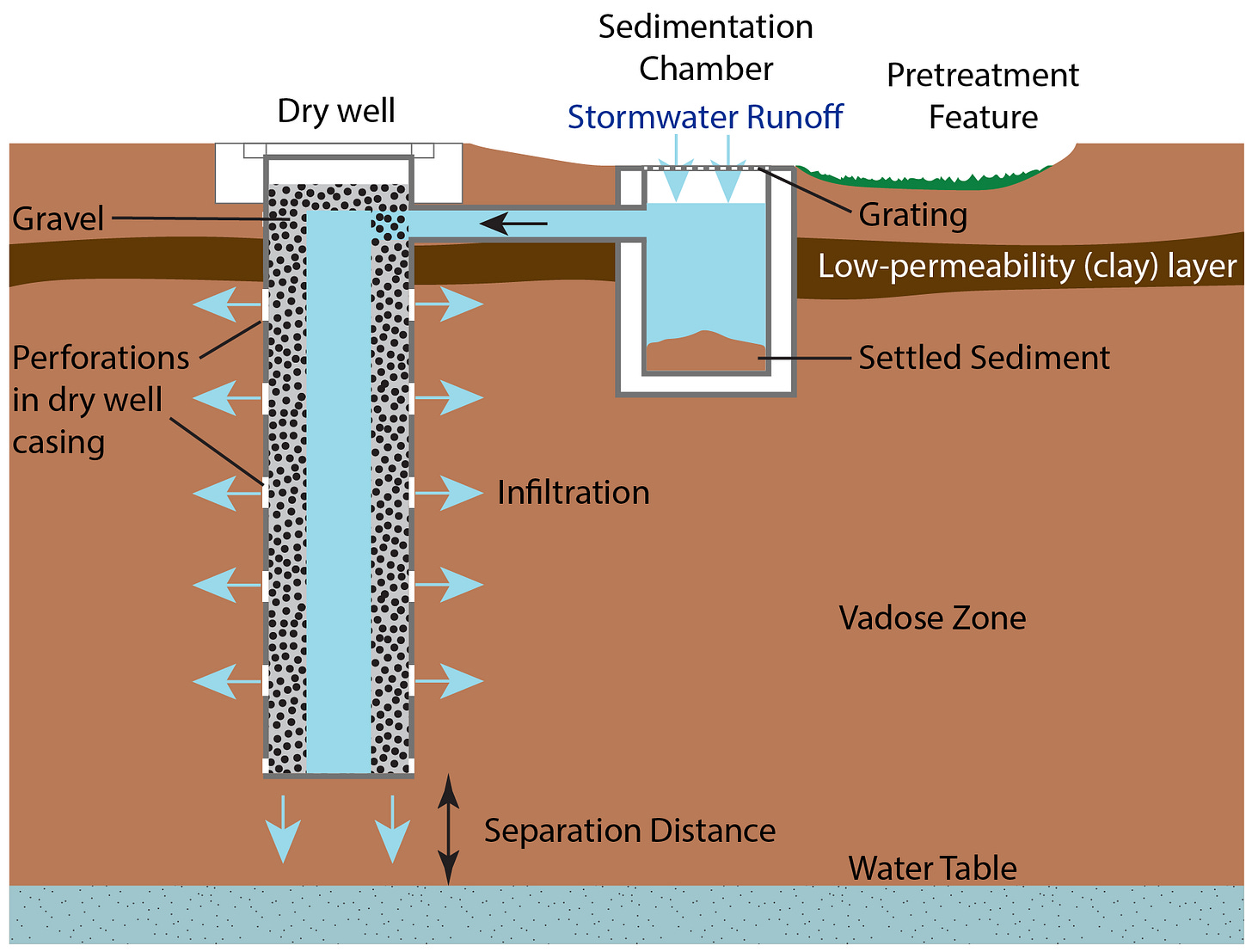

The pandemic has provided an exceptionally focused view into what drives policy decisions. Where ideology pulls in a different direction from science, for the pandemic the consequences become starkly evident in data. All-cause mortality is readily measured everywhere. Divergence from statistical prediction of the normal death rate in a country is well-understood math for statisticians and not hard to explain in everyday terms.

It’s possible to avoid a high case count by not testing, but excess mortality data shouts what happened anyway. We can see how well or how badly a government made choices and led its population by looking at that data. It doesn’t leave wriggle room.

The way German Chancellor Angela Merkel, a scientist herself, dealt with the arrival of the COVID pandemic was not surprising. She was calm, steady, rational, and clear in communications with the public and in making crucial decisions as the pandemic arrived.

But if the measure of success in facing the pandemic is the lowest per-capita number of excess deaths, New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern led a superlative national response. Although not a scientist herself, she listened to good advisors, understood them and based her decisions on facts rather than ideology. The results showed especially dramatically in the first year of the pandemic. The advantage New Zealand gained by fending off the pandemic until later than other countries still shows in cumulative death rate data today, dramatically lower than other countries, even though eventually they gave up on stringent pandemic restrictions like larger countries did.

This chart compares cumulative excess deaths among a few of the countries that fared best in this regard. We can see when each country eased up and how low numbers early on set up a lasting advantage.

(Chart from WixStatic based on figures from Our World In Data)

My countries, the USA and UK, have such high excess deaths that including them in the chart would squash the countries shown above into an indistinguishable muddle toward the bottom. It’s easier to see what happened by looking at smaller groupings of countries.

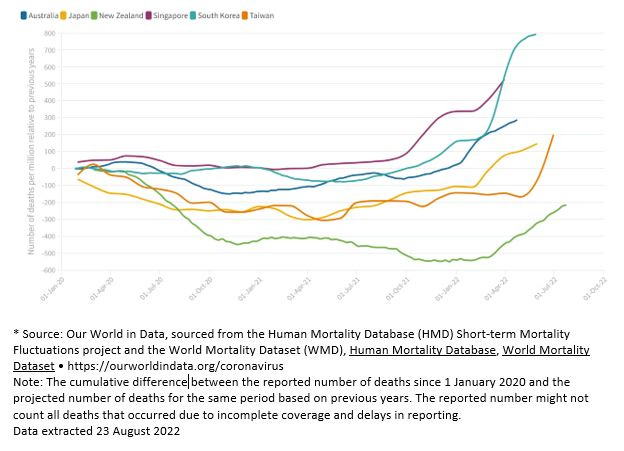

(Chart by Eric Muraille at ResearchGate)

Both of my countries went into the pandemic with detailed plans already prepared that were regarded as among the best in the world.

Both countries tossed out their plans. (Singapore implemented a copy of the UK’s plan. As we can see in the excess deaths data, that turned out well for them.)

It was no surprise that the Trump administration threw out its plan and refused to listen to scientists. It was more of a surprise in the UK, where government repeatedly told the public that pandemic response was “led by science.” A steady drip of information has undercut that story, but Isabel Oakeshott’s leak of Matt Hancock’s WhatsApp messages blew it to pieces.

Kit Yates is very much into math and science. His article in the Guardian about what the first tranche of messages reveals is worth reading.

Do you remember how old you were when you learned that 4% can also be written as 0.04? I can’t either. I’ve known it since I was such a little kid that I don’t recall how little I was.

The UK was being led by a Prime Minister who went to an elite school, but struggles with that concept. I won’t go into the rest of what he didn’t understand. Yates’ article does that. To summarize, whatever Boris Johnson learned wasn’t basic science or math. That’s how the UK got a pandemic response that has often gone against the advice of experts.

Not having enough of a basic foundation in science and math to distinguish between expertise and ideology was as damaging in the UK as intentionally disregarding expertise in the USA. We can see it in excess mortality data.

Every one of those excess deaths was a person, part of a family and circle of friends and community. Their premature deaths are calculable. The full harm of their loss is incalculable.

In Short

Without basic grounding in science and math, we’re easy marks for people promoting a fiction that’s convenient for them but contrary to the best way to cope with reality. We’re also easily misled by our own wishes into paths that aren’t viable.

We need basic science and math every day. It’s useful for all of us.

The higher the stakes, the more important it is.

Additional Resources

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)

Science Based Medicine: To put New Zealand, UK and USA all on one chart, we can look at the percentage difference between reported mortality and the average from pre-pandemic years. This is not an easy chart to understand. Think hard about the fact that it’s percentage difference, not raw numbers or per-capita numbers.

It's hard for me to fathom that, despite nearly all of the US and UK population completing at least 12 years of schooling, that so many of our citizens lack basic understanding of science. What are we doing wrong to educate our citizens? Why do they fall prey to the bloviators and politicians who convince them that they, rather than the scientists, are the experts, and that fear of government, of the CDC, of "mainstream media" is a bigger threat to their wellbeing? If only we had leaders who used their powers for good instead of evil.